Inside the Character, Part I: What Is Interiority?

How fiction learned to turn outward action into inner life—and why that shift still defines great storytelling.

(From my James River Writers lecture, “Inside the Character: Techniques for Writing Thought and Emotion in Fiction”)

A month ago, I had the pleasure of speaking at the wonderful James River Writers Conference here in Richmond. My session, “Inside the Character: Techniques for Writing Thought and Emotion in Fiction,” explored one of fiction’s most incredible superpowers: its ability to take us inside a character’s mind.

Unlike film, television, or theater, fiction doesn’t have to stop at what characters say and do. It lets us slip behind their eyes and into the currents of what they feel, remember, fear, and desire. We can inhabit a consciousness, not just observe it. That’s the beauty of prose modern storytelling—and also its most significant challenge. Because while it’s easy enough to show what someone does, it’s far harder to render what it’s like to feel like them, especially when emotions can be murky and constantly changing.

That’s what I wanted to unpack in the session—and what I’ll dig into here, across three essays. This first installment asks the simple but slippery question: what exactly do we mean by “interiority”?

Tracing the Turn Inward

Interiority is the representation of a character’s inner life—their thoughts, emotions, memories, sensations, and fleeting impressions. It’s not dialogue, not even internal monologue in the strict sense. It’s what’s beneath those things—the silent hum of perception and feeling that drives a person from moment to moment.

Storytellers didn’t always know how to do this. The earliest narratives—from epics and classical dramas to medieval romances—were primarily concerned with external action. Heroes fought, traveled, triumphed, and fell; the audience observed their deeds from the outside. Other than emotion filtered outwardly in speeches and monologues, the private self simply didn’t exist as a literary concern.

By the eighteenth century, the novel began to turn inward. Epistolary works like Pamela or Clarissa cracked open the door to interior life by presenting stories as letters or diaries—forms that naturally confessed. The nineteenth century flung that door wide. Jane Austen’s innovation of free indirect discourse—her subtle weaving of narration and thought—let readers slip in and out of a character’s consciousness almost imperceptibly. Tolstoy, the Brontës, and the great Victorians followed, deepening fiction’s psychological reach.

Then came Modernism, with its deliberate and far-reaching experiments in representing thought processes on the page. Joyce’s Ulysses, Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway, and Proust’s In Search of Lost Time made consciousness itself the terrain of fiction. Their characters no longer simply had interior lives—their interior lives were the story.

Contemporary fiction has inherited all of this. Whether it’s literary or genre, realist or speculative, we now expect our novels to let us inhabit a living, thinking mind. Interiority has become the medium’s defining strength, its distinguishing power over film or television.

Why this evolution? Because fiction began to care not just about what people do, but about why they do it. It sought to mirror the way our minds actually work—irrationally, emotionally, full of contradiction and half-articulated desire. The novel, in other words, wanted to represent not just the world but consciousness moving through it.

Why It Matters

Understanding interiority isn’t just a matter of style—it’s the foundation of point of view, or as William Sloane beautifully called it, a means of perception. He wrote in The Craft of Writing:

“The fiction writer is faced with the problem of deciding who, from the reader’s point of view, is telling the story; a narrator—the ‘I’ story—in which case the reader, following the story, simply becomes the fictional character who is the narrator; a central character who is told about by the writer, but as if the writer were serving for the reader; a series of characters, each of whom, in turn, perceives for the reader; or a never-named and omniscient narrator.”

In other words, interiority determines how the reader experiences the fictional world—through whose eyes, whose filters, whose emotional truth. Without it, we’re left with puppets on a stage. With it, we enter a consciousness, and that consciousness becomes our reality for the length of the story.

Sloane went further:

“In the best fiction and most of the time, the reader is identifying with one or another of the characters in the story. He is vicariously living the fictional life of that character. … What is important is that this is the fiction writer’s most useful device for securing the reader’s participation.”

That participation—that emotional alignment between reader and character—is what keeps us turning pages. We don’t read Jane Eyre for the plot alone; we read it because we feel the storm of Jane’s mind, her stubborn will and moral ferocity. We don’t follow Leopold Bloom through Dublin simply to map his route, but to experience how memory, shame, and longing shape every step he takes.

If you fail to convince the reader to care about your point-of-view character’s private experience—their thoughts, sensations, contradictions—you risk losing them. Action, dialogue, and description can carry a scene only so far. The inner current gives it meaning.

Point of view, of course, is a vast subject—an entire semester’s worth of headaches and exciting discoveries—but for our purposes, I’m narrowing the lens to the two perspectives that most directly shape interiority in modern fiction: first person and third-person limited omniscient.

In Part II, we’ll explore how each handles consciousness—how close they bring us to the mind’s edge, how to balance immersion with clarity, and how to use interiority to create truly vivid, emotionally resonant scenes.

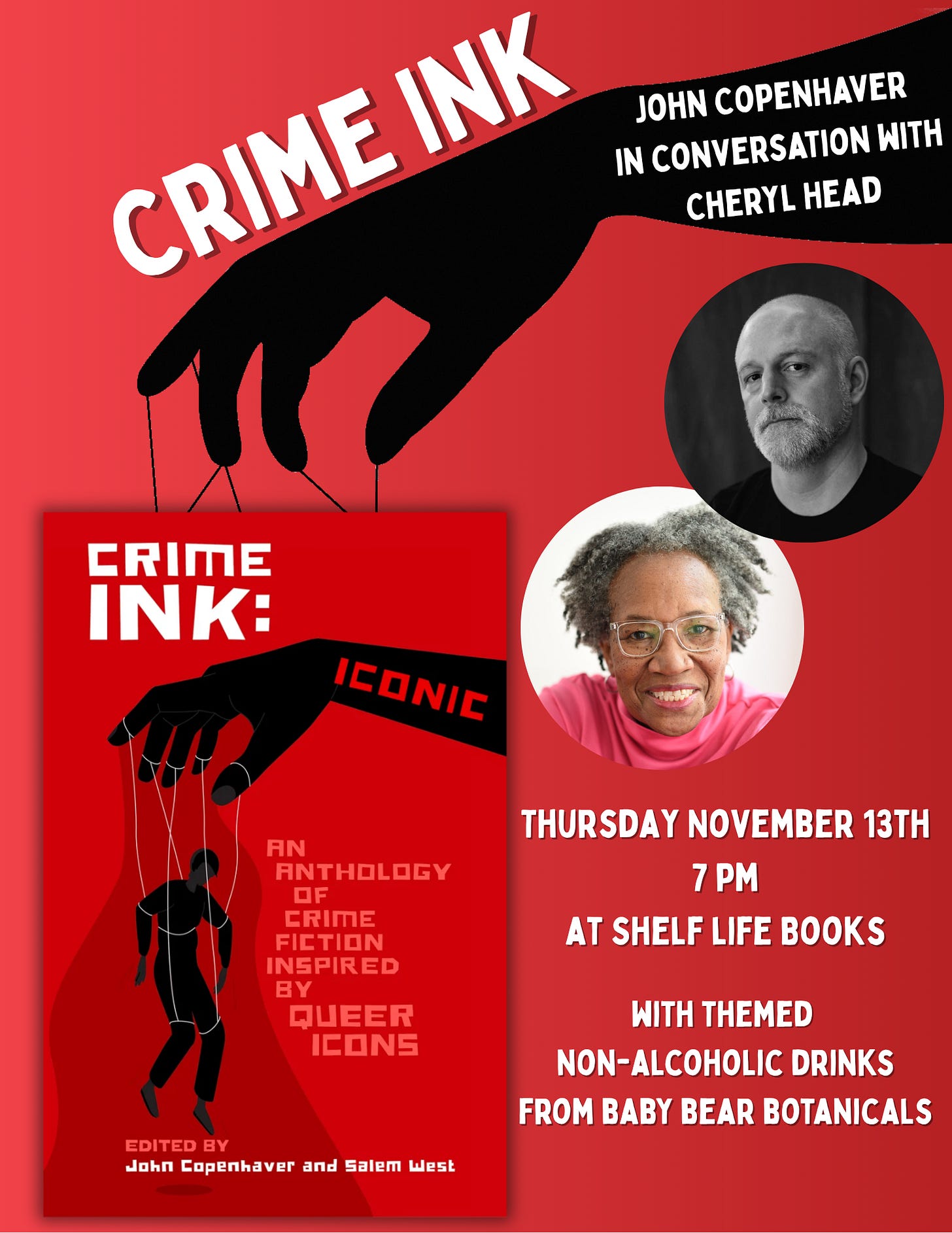

Wrapping the Crime Ink: Iconic Tour at Home

This is it—the final stop of the Crime Ink: Iconic tour—and I couldn’t be happier to wrap it up close to home.

On Thursday, November 13, at 7:00 PM, I’ll be at Shelf Life Books in Richmond in conversation with the wonderful Cheryl Head about this groundbreaking anthology of queer crime fiction I co-edited with Salem West.

🎟️ This is a ticketed event, so grab your spot early. Click here.

Recently, Women Using Words ran a terrific review of the anthology that truly captured what we were striving for:

“Beyond its stylistic range, Crime Ink stands out for its depth. The collection is memorable not for the crimes themselves but for what they reveal. The strongest stories dig beneath the surface, exploring why people cross lines, betray their better selves, or cling to impossible ideas of justice. Most significantly, they peer into the murky space between moral conviction and human frailty through the lens of the queer experience, touching on secrecy, defiance, survival, and the cost of authenticity.”

That’s the heart of what we hoped to accomplish—crime fiction that isn’t just about transgression, but about what it costs to live truthfully in a world that often punishes authenticity.

And since every good Richmond event deserves a local flourish, Baby Bear Botanicals will be serving up themed mocktails, and my husband, Jeffery Paul Herrity, is whipping up a sweet treat to go with them.

Now more than ever, it’s vital to support queer voices and the stories that push back against silence. Come for the conversation, stay for the community.

You are the amazing teacher and writer I need at this moment as I shift from writing exclusively nonfiction to first-person POV in fiction. Love this history and look forward to the next two installments! Thanks