On Taking Different Paths to Publishing (Part III)

Ernie’s Journey & the Reunion

Ernie’s Journey & the Reunion

This is Part III of “On Taking Different Paths to Publishing.” If you’re new, start with Part I and Part II. That’s where Jane and Nella’s stories unfold. Now it’s Ernie’s turn—and then we’ll bring all three back together.

Chapter 4: Devil’s Elbow (Ernie’s Story)

During his MFA, Ernie writes a series of stories inspired by his hometown, each throwing light on an unusual character in a fictional Appalachian community called Devil’s Elbow. A boy navigating his first crush. A woman pawning her wedding ring to keep the lights on. A preacher wracked by doubt. Ernie ties them together into a collection—a novel-in-stories that shows his community “warts and all,” with poverty and hardship, yes, but also self-awareness and love.

He knows the obstacles. Agents rarely represent short story collections: they’re hard to sell, and the 15% commission on a $3,000 advance hardly keeps the lights on. But Ernie believes in the work.

He builds a meticulous spreadsheet with three tabs:

Literary magazines

Contests

Conferences and residencies

He subscribes to Poets & Writers, checks NewPages.com, and sets up a submission schedule. He uses Submittable and Tell It Slant to track submissions, always keeping ten stories out at once.

At first, only form rejections arrive. But slowly, stories start landing in small journals. Each one is a lifeline.

At AWP, Ernie reads with other MFA alums in a crowded hotel bar. Beer bottles clink. They reminisce. Afterward, he chats with an alum now working at a well-regarded literary magazine. Ernie is careful not to be pushy. He asks about her work first, then mentions his. She invites him to submit. Back home, he sends his strongest story with a personal note. A month later, the magazine accepts it. He’s thrilled.

Encouraged, Ernie applies to high-profile workshops—Tin House, Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference—knowing they offer access to agents and editors. Tin House rejects him. Bread Loaf admits him, but without financial aid. Ernie hesitates. He grew up poor, is debt-averse, and lives modestly. But he has savings. He decides to invest in himself.

At Bread Loaf, he attends dynamic workshops, mingles with peers, and nervously takes his agent meetings. One agent—impressed by his quiet, precise prose—requests the manuscript. She admits she won’t make much money selling a collection but believes in short fiction and in diversifying her list.

Within six months, she sells Devil’s Elbow to a small but robust independent press for a $4,000 advance. The press—like Catapult, Coffee House, or Soho House—is well-regarded for supporting innovative short-form fiction and nonfiction.

The press has a publicist and a modest marketing budget. Coverage of Devil’s Elbow is limited but warm. Reviews describe it as compassionate and unflinching. Ernie wins the Flannery O’Connor Award for Short Fiction and is a finalist for others.

He’s proud. Secure in his identity as a short story writer. But sales are meager. His agent and publisher, while supportive, hint not too subtly: The next one should be a novel.

Ernie tries. He outlines. He drafts. But the words feel wrong. His stories breathe in 15 pages, not 300. Short fiction is his native tongue. Still, he hears his agent’s voice: “I know you have a novel in you!” Which he translates as: Write a novel or find another agent.

When Jane emails about a Zoom happy hour, Ernie—despite his dislike of Zoom—says yes. He needs his friends.

Chapter 5: The Reunion

The Zoom call runs two hours. They slip easily back into old rhythms. Each vents. Each listens. Each reminds the others why they write.

Jane, deflated by disappointing sales, admits she hears her parents’ voices in her head. Nella and Ernie remind her she’s already achieved so much and gently point out her privilege.

Nella, pressured to write “to market,” wonders if they’re betraying their voice. Jane and Ernie encourage them to resist, to keep writing the radical, joyful work that brought them here.

Ernie, paralyzed by the demand to write a novel, shares his frustration. Jane and Nella suggest strategies: building a novel from interconnected stories, experimenting with braided narratives, reimagining his short-form sensibility on a larger canvas.

They leave the call energized, grateful, and recommitted. Jane proposes they make it a monthly habit. They all agree.

Chapter 6: Happy-ish

So there you have it: the story of three writers.

Jane with her auctioned debut and the crushing reality of sales numbers.

Nella, with their self-publishing grit, indie press breakthrough, and unease about being nudged toward the market.

Ernie with his quiet, award-winning story collection and the relentless pressure to become “a novelist.”

Three writers. Three different paths. Each publishing. Each validated. Each, in their own way, struggling.

And here’s the truth: they are not happy. Not exactly. They are happy-ish.

Why the “ish”? Because writing never stops demanding more. It never stops asking you to persevere, to stay vulnerable, to reinvent yourself again and again. The “success” you think will finally silence your fears never does. Jane still hears her parents telling her she’s wasting her life. Nella still feels the temptation to bend their voice toward the market. Ernie still wonders if he’s doomed because he can’t stretch his stories into a novel.

Publishing is not glamorous. Glamour belongs to influencers and advertisers, not writers. Glamour has nothing to do with sitting alone in a room wrestling a paragraph into shape.

What publishing does teach—sometimes harshly—is that you must study the market. A book is judged by its cover, and in our capitalist system, you must be conscious of audience and presentation. But here’s the paradox: listen too closely to the market, and you risk losing your voice.

Fear is the writer’s greatest enemy. Not rejection letters. Not small sales figures. Fear. Fear of not measuring up, of failing, of wasting your life. Fear blocks creativity—or worse, diverts it down the wrong path.

Financial security matters too. Jane, cushioned by privilege, can afford risk. Nella and Ernie cannot. But none of them let their day jobs erase their creative drive. The lesson isn’t “quit everything and write.” The lesson is: don’t let the pursuit of security extinguish your art.

Because here’s the truth: the day-to-day of publishing is often unremarkable, sometimes dispiriting. You’re writing emails, filling spreadsheets, sending queries, and reading rejection letters. You’re watching other writers seem to “leap ahead.” You’re waiting—always waiting—for a response. And if you measure your happiness by external metrics—advances, reviews, starred trade journals—you’ll be disappointed.

Happiness isn’t guaranteed. It isn’t deserved. It isn’t even the right goal.

My mother, a frank and redoubtable woman, once told me, over a glass of wine:

“John, whoever told you, you deserved to be happy?”

I winced when she said it. Harsh, right? But as the years passed, I realized what she meant: stop chasing happiness as if it’s a right owed to you. Stop waiting for the day when everything clicks and the industry crowns you “successful.” That day may never come. And if it does, it will be fleeting.

Instead, find joy in the work itself. In the drafting, the revising, the discovery. In the sustaining friendships you make with other writers. In the small moments of affirmation—a glowing reader email, an unexpected review, a line that finally sings on the page.

As that bubbly optimist Friedrich Nietzsche once remarked:

“A good writer possesses not only his own spirit but also the spirit of his friends.”

Writing may be solitary, but publishing is collective.

Behind every book is a community—teachers, peers, mentors, editors, agents, spouses, friends. Every book has many authors, even if only one name is on the cover.

Jane, Nella, and Ernie—each on their own path, each leaning on one another—remind us that writing is a lifelong practice, not a destination.

The goal isn’t some mythical state of “happiness.” The goal is to keep going. To keep writing. To remain, against all odds, happy-ish.

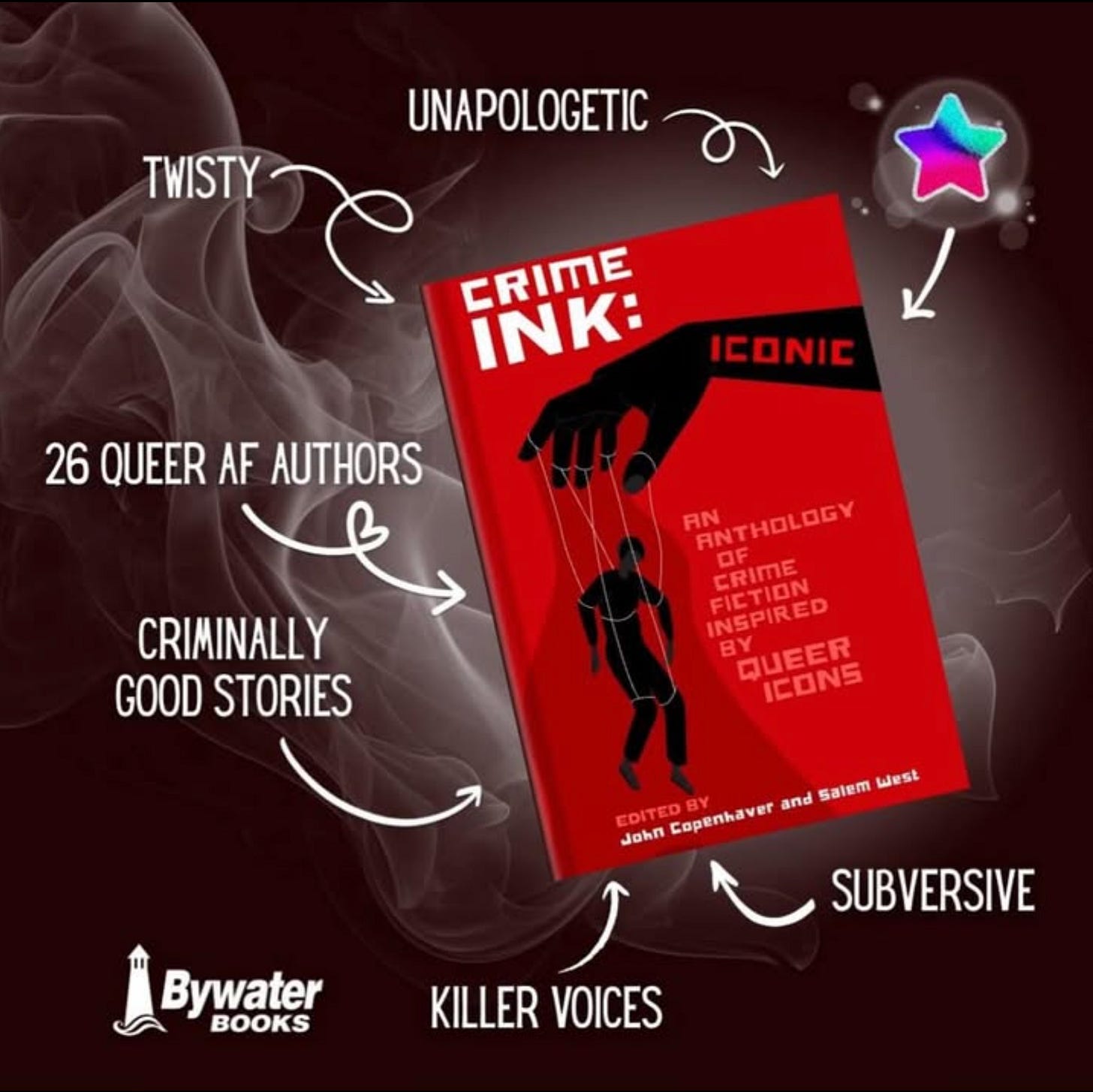

In 2023, out of 517 stories published in major crime anthologies, fewer than 1% came from LGBTQ+ writers. That erasure is real—and it’s time to change it. Crime Ink: Iconic is our answer. Order now.

This anthology gathers crime stories inspired by queer icons—James Baldwin, Radclyffe Hall, Megan Rapinoe, Oscar Wilde, Candy Darling, and more—spanning everything from noir to cozy to psychological thriller. With a foreword by Ellen Hart and an afterword by Katherine V. Forrest, it’s both a celebration and a call to action.

Edited by Salem West and me, with contributions from some of the finest queer crime writers working today.

"Instead, find joy in the work itself. In the drafting, the revising, the discovery. In the sustaining friendships you make with other writers. In the small moments of affirmation—a glowing reader email, an unexpected review, a line that finally sings on the page."

OMG YES. OBSESSED WITH THIS ADVICE THANK YOUUUUUUU.