Reckoning with Problematic Writers: Can We Separate Art from the Artist?

Navigating the ethics of teaching authors who have left an indelible mark on literature—while also carrying deeply troubling legacies.

This week, once again, in my Queer Literature class at Virginia Commonwealth University, I’m preparing to introduce a unit on Patricia Highsmith. In this class, I teach The Price of Salt (or Carol), and last fall, in my Introduction to Crime Fiction course, I taught The Talented Mr. Ripley. Most would agree that Highsmith is essential reading for students of queer fiction and crime fiction. I have a foot squarely in both avenues of study—as a writer of queer crime fiction myself.

Stylistically, Highsmith is the queen of unease. No other writer tightens the screw as skillfully, ratcheting up tension by degrees—she doesn’t go for a quick stab but slips the knife in slowly, leaving you doomed before you even realize what’s happened. In The Talented Mr. Ripley, we’re lured into Ripley’s world, made complicit in his crimes, cheering for a murderous psychopath by the end and wondering—where did my moral foundation go? And with The Price of Salt, a much tenderer but no less unsettling novel, you’re wrapped up in a passionate lesbian romance and coming-of-age story, unprepared for the sacrifices these characters—especially the stylish housewife Carol—must make to be freely herself. Highsmith’s fiction forces us into complex moral terrain, and while uncomfortable, it’s a valuable place to go. Indeed, her work prompts us to reflect on our own moral foundation, forcing us to humbly question its stability.

But Highsmith herself was, to put it mildly, problematic. She drank like a fish, tore through romantic relationships with women—passion at the beginning, chaos at the end—all fueled by an unhappy childhood. Her relationship with her mother, Mary Coates Plangman, was particularly toxic. As Rennie McDougall explains in The New York Times Style Magazine article “The Many Faces of Patricia Highsmith,” Mary once “joked” that Highsmith loved the smell of turpentine because she had drunk it while pregnant, hoping to miscarry. McDougall also notes,

“[Highsmith] once wrote an outline for a story in which a young girl tenderly puts her mother to bed before taking out a pair of scissors and plunging them into the woman’s heart, smiling.”

Mary sent Patricia cruel letters, and Patricia responded by blaming her for her “character defects, including her queerness.”

Highsmith flung her unhappiness outward and inward. In her journals and to friends, she was an unapologetic anti-Semite (who dated a Jewish woman), a racist, a misanthrope, and a skeptic who teetered between religious belief and disbelief. She seemed to offend from every angle, only to destabilize her position the next. It was as if she were never on sure footing about what she believed—perhaps stemming from a lack of clarity about who she was.

All this is to say: I continue to teach Highsmith despite her abhorrent views because, in my field and as a writer, I recognize her as a key figure in both queer and crime literature. However, I teach both the brilliance and the flaws, presenting them as essential to understanding and discussing her work.

For very understandable reasons, there’s been an ongoing debate about how to handle disgraced writers. My colleague A. Rafael Johnson (author of The Through) at the University of Nebraska Omaha—where I mentor in their low-residency MFA program—proposed a panel on how teachers, readers, and writers should approach authors who have done significant harm. We compiled a long list of infamous dead and living writers.

Among the dead: Alice Munro, the Nobel laureate who, we now know, turned a blind eye to the sexual abuse of her daughter, Andrea Robin Skinner. And Patricia Highsmith, of course.

Among the living: J.K. Rowling, who has wielded her immense influence to cultivate hatred against the trans community and refuses to relent. Comedian Bill Cosby, bestselling author of Fatherhood, a convicted serial rapist whose case was frustratingly overturned in 2021. Alice Sebold, author of The Lovely Bones, who wrongly accused Anthony J. Broadwater of rape, sending an innocent Black man to prison for sixteen years. And, most recently, Neil Gaiman—news of his alleged crimes was trickling in at the time of the panel, the Vulture exposé detailing them in full had yet to be released.

With dead authors like Highsmith, it’s easier to proceed. You can tell the whole story—the good, the bad, and the outright ugly—and let college students wrestle with their feelings. Claire Dederer, in her brilliant meditation Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma, suggests that how we respond to a problematic artist is personal. It can’t be codified or made absolute. However, individual reactions should be honored.

But when it comes to the living—especially those who are enablers of child abuse, vicious rapists, racist false accusers, or peddlers of dangerous untruths—it’s impossible to imagine teaching them in the classroom despite their literary importance.

Have they left an indelible mark on literature and culture? Absolutely. It’s hard to argue that Munro, Rowling, Sebold, Cosby, and Gaiman haven’t shaped our collective imagination—there’s no escaping their influence. But beyond their crimes, perhaps the most troubling question is this: by loving their work, even unknowingly, have we been complicit? I don’t know if I believe that—but I do believe it’s a question worth asking, even if there’s no clear answer. As with reading Highsmith, it’s important to approach our moral self-understanding with humility, recognizing that no one is entirely impervious to corruption.

Someday, we may have to reckon with their legacies. Perhaps once they’re dead. I’m not a believer in erasure—even of the bad. We need to remember their crimes and learn from them. (It’s worth noting that we learned of Munro’s betrayal of her daughter only after her passing, which has already prompted a wave of reassessments of her work—like the excellent New York Times Magazine article What Alice Knew by Giles Harvey. Ultimately, she will resurface—like Highsmith—but with a complicated shadow over her legacy.)

For now, though, I can’t imagine reading her. And I’ll always honor those who choose to turn away from these writers—and never look back. That, as Dederer suggests, is a valid response that we educators should honor—and prepare for.

In Other News!

So, for something that has NOTHING to do with disgraced authors!

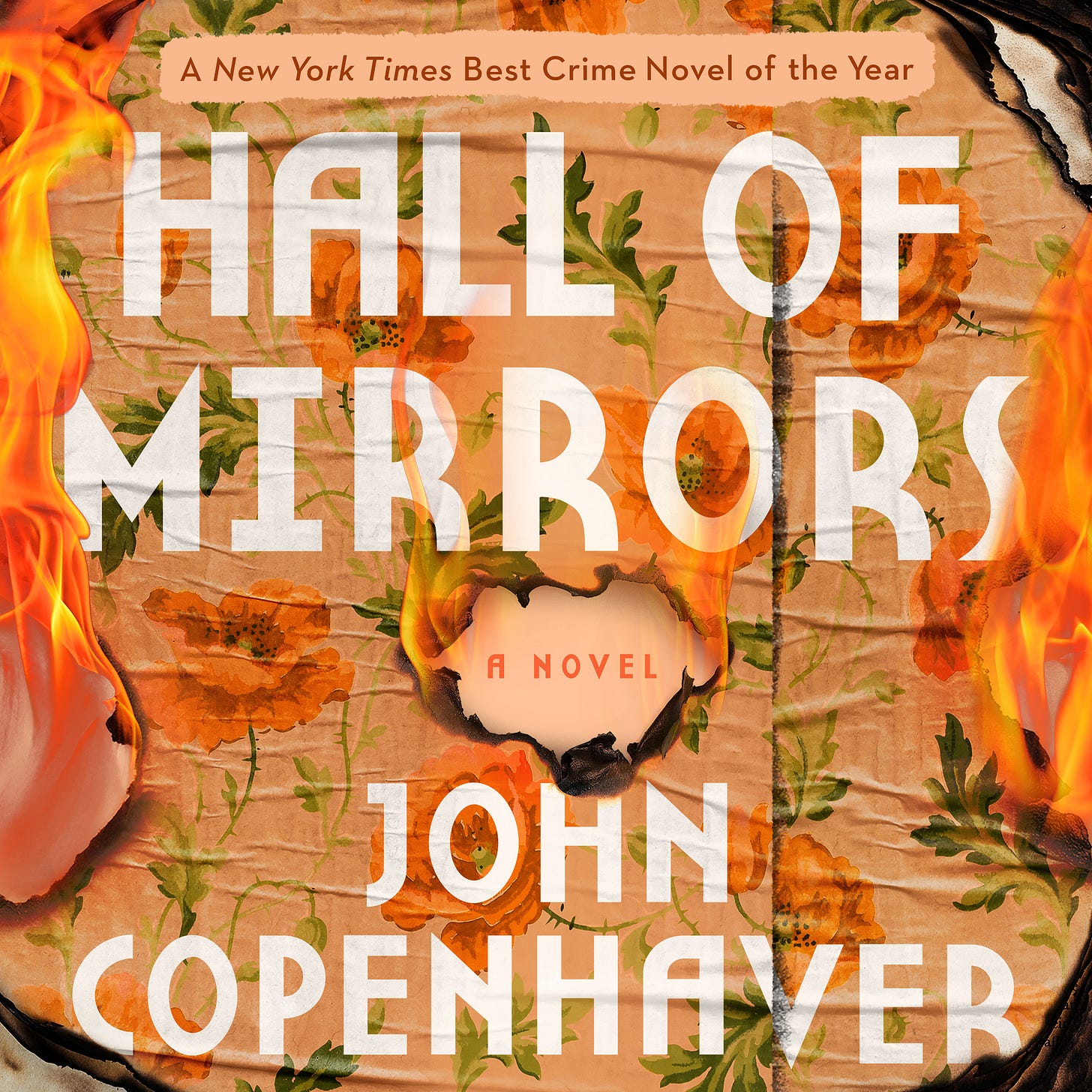

Hall of Mirrors is out on audio, and I couldn’t be more excited! I’ve always loved audiobooks that pull you in, and this one truly does—thanks to the incredible work of Deyan Audio and the phenomenal performances of Sion Dayson (Judy), Ray Ford (Lionel), and Shea Taylor (Roger).

Hearing my words come to life like this is surreal, and I can’t wait for you to experience it.

Hall of Mirrors is available now wherever you listen to audiobooks! Let me know what you think.

I really appreciate that you’ve taken on this complicated idea. Dad often talked about the difficulty of reading the work of theologians who were later found to be morally reprehensible. What do we do with their theologies —particularly after we’ve been sifting through their ideas for fifty or a hundred years? I’m very excited about all of the accolades that have come your way for your work! Congratulations!

I’ve been going back and forth over what to do with my copy of THE WOLVES IN THE WALLS, a children’s picture book by Gaiman and illustrated by Dave McKean. My 5-year-old niece has asked for back-to-back readings and I totally understand why: the narrative is giving her space to examine her real-life fears, and there’s a message of self-determination, with a point (not made nearly often enough) that the grown-ups aren’t always the most sensible people in the room. Someday, when my niece is old enough, I will tell her some pertinent facts about the author. So thanks, John…I think you’ve just convinced me not to burn it. 😬