The Writer’s Task: To Capture Feeling in Flux

On crafting characters who live in contradiction and change

If we want to write fiction that feels true, we must create characters who, in their interior lives, experience ambivalence. We’re human—ambivalence is part of our emotional landscape. And yet, again and again, I read stories where characters are flattened into types, their emotional journeys arrow-straight, or forced into clarity at the climactic moment, producing a convenient sense of “before” and “after”: I was blind, but now I see.

I think this is, in part, a product of the times we live in. Social media rewards certainty, simplicity, and outrage. You’re either this or that, for or against. There’s no room for contradiction, no patience for doubt. Everything becomes binary. And I get it—it’s hard to metabolize complexity in a world moving at a dizzying speed. But fiction can—and should—push back against that. As fiction writers, it’s our duty to the craft.

In fiction, we need to dwell in uncertainty. In contradiction. In the in-between. That’s where the emotional heat is. That’s where real tension, complexity, and genuine humanity reside.

Recently, during a book group Zoom visit, one of the readers of The Savage Kind, the first book in my Nightingale Trilogy, shared that she initially had trouble connecting with the characters—particularly Philippa. She found it difficult to get a clear read on her early on, especially in the way Philippa’s feelings about Judy seemed to shift or remain unresolved. I understood the reaction, but to me, it was a sign that the story was doing what I hoped it would. I wanted to show what it feels like not to be sure—when you’re still testing the boundaries of your identity, your desires, and the people around you.

There’s a moment early in the novel that exemplifies this kind of emotional exploration—Philippa observing Judy and feeling both drawn in and thrown off:

“Welcome to paradise,” floated from her [Judy’s] lips, tinged with scorn. But the heat of her glare had been replaced with something else. Confusion? Curiosity? I wasn’t sure. Then suddenly, violently, she smiled. It was a cool, inscrutable smile, but all the same, it gave me a strange shock, like accidentally catching your reflection in a mirror. I felt seen by her—or was it that she’d seen some hidden part of me that the others hadn’t? It was horrifying and thrilling, and I was temporarily struck dumb.

That blend of confusion and curiosity—of watching someone else closely while also becoming aware of yourself in the process—is what interests me. Especially with teenagers, emotional states aren’t fixed; they’re exploratory. As Philippa later puts it:

“Adults, it seems to me, think teenagers hide things from them to cultivate our private lives and stake out our individuality. That’s not entirely true. Most of the time, we don’t know what to tell them. We know we aren’t who they think we are, and we suspect we aren’t even who we think we are, because we aren’t who we were a month ago, a day ago, a minute ago. We’re too busy becoming something else, molting into something new, to know what that is. In that fragile limbo, so much can happen; so much can be discovered, so much can be destroyed.”

Ambivalence doesn’t mean a character is poorly drawn or indecisive. It means they’re emotionally alive. They can love someone and hate them. They can want something desperately and be terrified of having it. They can lie to themselves and tell the truth in the same breath.

Take Nick Carraway in The Great Gatsby. Reflecting on his feelings for Jordan Baker, he says:

“I wasn’t actually in love, but I felt a sort of tender curiosity.”

He doesn’t quite know what he feels—and that not knowing is the most honest part of it. That emotional haze is more convincing than declarations of certainty.

After hearing of Septimus Smith’s suicide, Clarissa Dalloway in Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway steps away from her party to reflect on his death. Though she never met him, the news deeply unsettles her. In that quiet moment, she senses a kinship with him—an understanding of his despair, and perhaps even an admiration for the boldness of his final act:

“She felt somehow very like him—the young man who had killed himself. She felt glad that he had done it; thrown it away. The clock was striking. The leaden circles dissolved in the air. He made her feel the beauty; made her feel the fun. But she must go back. She must assemble.”

His suicide becomes, for her, not just a tragedy, but a radical assertion of autonomy. It stirs in her a heightened awareness of life’s intensity and fragility. And yet, she returns to the party—to her performance. There is no tidy “before and after” here, but rather a flicker of revelation, a fleeting recognition of what it means to be alive. This rising to insight and then slipping away from it isn’t a flaw in the novel—it’s its soul.

And then there’s Briony Tallis in McEwan’s Atonement, near the end of her life, reckoning with her past and the devastating consequences of her youthful mistake. Now a successful writer, she confronts the limits of her art and the impossibility of true redemption through storytelling alone. Reflecting on her final novel—her last attempt to make things right—she writes:

“How can a novelist achieve atonement when, with her absolute power of deciding outcomes, she is also God? There is no one, no entity or higher form that she can appeal to, or be reconciled with, or that can forgive her. There is nothing outside her. In her imagination she has set the limits and the terms. No atonement for God, or novelists, even if they are atheists. It was always an impossible task, and that was precisely the point. The attempt was all.”

This moment does so much—it carries guilt and sorrow, yes—but also a kind of surrender. Briony acknowledges the futility of her effort, even as she embraces it. There’s no true atonement possible—not for her, not through fiction—and yet that doesn’t mean the effort is meaningless. In fact, the striving itself becomes the moral act. She is fully alive in the tension between responsibility and powerlessness, invention and truth.

And finally, consider the remarkable final paragraph of W. Somerset Maugham’s The Razor’s Edge. The narrator, a fictionalized Maugham, reflects on what kind of story he’s told:

“But as I was finishing this book, uneasily conscious that I must leave my reader in the air and seeing no way to avoid it, I looked back with my mind's eye on my long narrative to see if there was any way in which I could devise a more satisfactory ending; and to my intense surprise it dawned upon me that without in the least intending to I had written nothing more nor less than a success story. For all the persons with whom I have been concerned got what they wanted: Elliott social eminence; Isabel an assured position backed by a substantial fortune in an active and cultured community; Gray a steady and lucrative job, with an office to go to from nine till six every day; Suzanne Rouvier security; Sophie death; and Larry happiness. And however superciliously the highbrows carp, we the public in our heart of hearts all like a success story; so perhaps my ending is not so unsatisfactory after all.”

Here, the fictionalized Maugham reflects on desire and the nature of fulfillment. Not all of the characters achieve what we’d traditionally call a successful outcome—but perhaps they do get what they truly wanted. He isn’t exactly ambivalent; rather, he lives within paradox, dwelling in a liminal space that resists binary thinking. And that, I think, is something to strive for.

So, when I work with students or write my own fiction, I always try to remember that certainty is not the goal. Ambivalence is not a problem to be solved—it’s a condition to be explored and described with care. It’s what makes characters feel human. It’s what gives stories depth.

When you let your characters live in that space between clarity and confusion, between love and fear, belief and doubt, you’re writing something that can’t be summed up in a post.

And that’s a good thing.

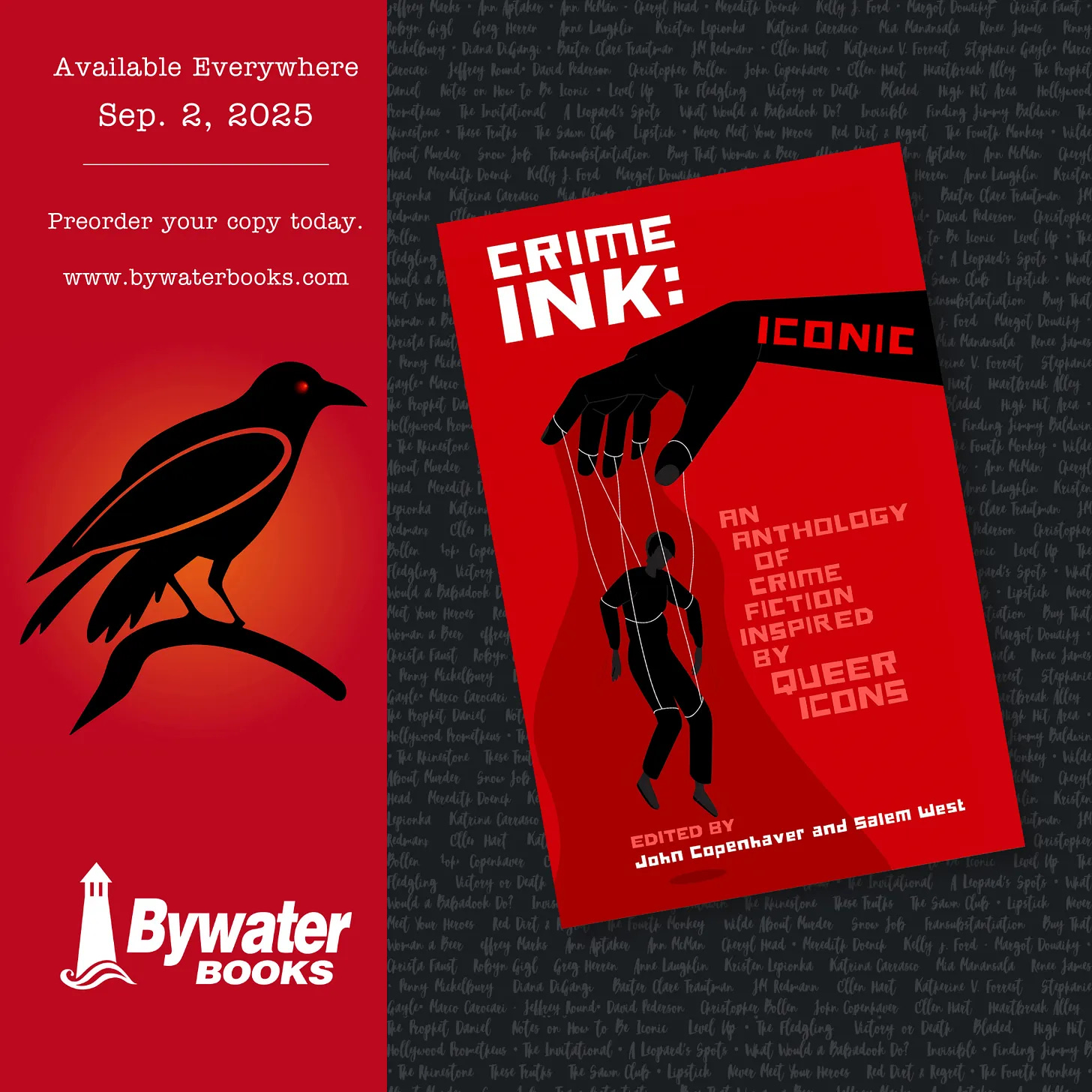

Claim Your Copy of Crime Ink: Iconic—Preorder Now!

Salem West and I are excited to continue spreading the word about Crime Ink: Iconic.

This anthology showcases the full range of crime fiction—from noir to cozy, procedural to psychological thriller—united by bold queer voices and emotionally resonant storytelling. Every story is sharp, surprising, deeply human—and plenty of rich characterization and ambivalence! (Haha.)

But this book isn’t just a celebration of genre—it’s a reclaiming of space. At a time when LGBTQ+ stories are being challenged and erased, promoting this work feels less like marketing and more like resistance.

We’d love your help getting the word out. Preorder it, share it, champion it. Your support doesn’t just boost this collection—it helps make space for future volumes, emerging voices, and a more inclusive vision of what crime fiction can be.

There is no binary. We all live on the spectrum.